About Adolf Hungrywolf

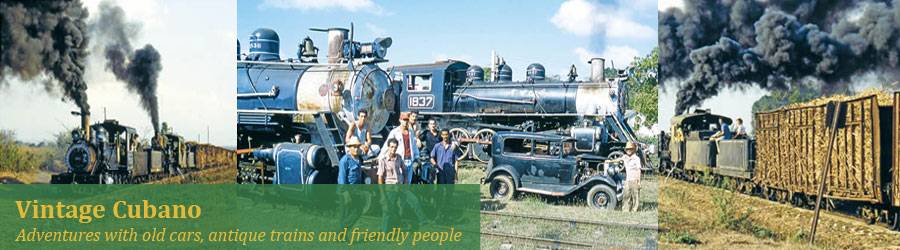

After more than fifty titles since 1969, Adolf Hungry Wolf of Skookumchuk, born of Swiss and Hungarian parents, is easily one of B.C.’s most unusual and prolific self-publishers. His many Aboriginal titles culminated in a massive, four-volume history of the Blackfeet, entitled The Blackfoot Papers (2006), and his appetite for travel and railroading, after twelve visits to Cuba, resulted in a remarkable pictorial overview of vintage railroads in Cuba, Vintage Cubano (Canadian Caboose Press / Hayden Consulting $75 U.S.). Vintage Cubano contains more than 1,000 images of most American-built trains and autos from the 1920s, ’30s, ’40s and ’50s. With this volume in 2012, the author altered the spelling of Hungry Wolf to Hungrywolf.

Born as Adolf Gutohrlein in southern Germany in 1944, to a Swiss father, also named Adolf, and a Hungarian mother, he never met his grandparents. At age ten he moved with his parents to California. With earnings from his paper route, he bought a plot of land in the mountains and began listening to the stories of an elderly Indian couple. He jettisoned plans to become a lawyer and began studying Aboriginal history at university, visiting tribes in the U.S. and Alberta. His first publication about railroading appeared in 1964; his first book about back-to-the-land spirituality, in 1969, marked the beginning of his Good Medicine imprint and his immersion in Aboriginal culture. He began dressing in moccasins and braiding his hair. While eating stew with an Indian family one night, someone remarked he ate like a hungry wolf. He legally changed his name to Adolf Hungry Wolf.

At a Blackfoot powwow in Montana he met Beverly Little Bear, from the Blood Reserve near Fort McLeod, who had been attending college in Lethbridge, Alberta. They married a year later and spent two years in an old log home on the Blood Reserve, near the home of her parents. They moved to British Columbia to live at their Good Medicine Ranch at Skookumchuck Prairie in 1973. As their four children were added to their family (Wolf, Okan, Iniskim and Star), he obtained a 1922 CPR caboose to serve as his office and publishing headquarters. He assembled a massive archive of 20,000 photos pertaining to Blackfoot culture and continues writing and publishing his own books at a remarkable pace. Their children took correspondence courses and helped in the mail order operations of Good Medicine Books and Canadian Caboose Press. Their acreage became home to the Rocky Mountain Freight Train Museum, consisting of four cabooses and five vintage boxcars. Hungry Wolf and his son Okan developed a series of railway videos. Some of his titles have been re-issued by large publishing houses, including Warner Books, Harper & Row, Verlag Sauerlander of Switzerland, Hernov of Copenhagen, Sherz of Munich, etc. In the 1990s his trips to Cuba resulted in a series of titles about Cuba and its railways. He and his family left Skookumchuck for several years in Alberta, but he has since returned.

Good Medicine is the theme of my life.” — Adolf Hungrywolf

Hungry Wolf has become an important leader in Blackfoot ceremonies, trusted as a keeper of medicine bundles, yet he is continually victimized by superficial attacks on his character by people who have never met him. He says he avoids seeking publicity in deference to teachings from Native elders. “I feel free to go along with p.r. when it comes my way,” Hungry Wolf says, “but not to actively seek it out.” Hungry Wolf is also leery of those who would denigrate his beliefs. Once stung by a reporter at the Frankfurt Book Fair who dubbed him a “Teutonic Grey Owl,” he has been the subject of a “wanted poster” circulated by a militant Aboriginal group in the 1970s and more recently he’s been called a “plastic shaman” by Greg Young-ing of Penticton. “To all that,” he replies, “I’m happy to say that my wife, children and I continue to be keepers for two of the Blackfoot tribe’s sacred medicine bundles, whose teachings regarding life in harmony with nature we’ve been learning for the past 30 years… Through all these years of attending the tribal ceremonials, we’ve never seen any of our critics there, so I’m left to wonder upon what they base their comments about our cultural life.”

His books include Good Medicine: Life in Harmony with Nature (1969), Legends told by the Old People (1972), The Blood People: A division of the Blackfoot Confederacy: An Illustrated Interpretation of the Old Ways (1977), Blackfoot Craftworker’s Book (1977), Rails in the Canadian Rockies (1979), Canadian Railway Scenes, No. 1 (1983), Shadows of the Buffalo: A Family Odyssey Among the Indians (1983), Shadows of the Buffalo (1985), Children of the Sun: Stories by and About Indian Kids (1988), Canadian Railway Scenes (1988), Canadian Sunset: A Farewell Look at America’s Last Great Train (1991), A Good Medicine Collection: Life in Harmony With Nature (1991), Tradition Dress: Knowledge and Methods of Old-Time Clothings (1991), Canadian Railway Scenes (1991), Blackfoot Craftworker’s Book (1991), Indian Tribes of the Northern Rockies (1991) and Trains of Cuba: Steam Diesel and Electric a Guide Book With Photos Maps Rosters and Detailed (1997).

Fifteen of Adolf Hungrywolf’s approximately fifty books are about railroading, including Vintage Cubano: Adventures with Old Cars, Antique Trains, and Friendly People (Hayden Consulting $60 U.S.), a retrospective gathered from 1993 to 2005 when he spent 18 months in Cuba. He recorded hundreds of narrow-and standard-gauge locomotives and countless old American cars for a 320-page, all-colour book. Hungrywolf took his first photo of Canadian railroading in 1963, at age nineteen, of a steam locomotive having its tender filled from a wooden water tank along a forest branchline on Vancouver Island. Since then he’s taken thousands of photos of Canadian railroading, and gathered thousands more, dating back to the 1870s. He intends to produce a cross-Canada magnum opus on railroading called Vintage Canadian, showcasing 600 colour slides and 800 b&w photos.